Fiscal spending reforms – if not now, then when?

All four large CEECs that joined the EU in 2004, have had problems with fiscal deficits in excess of 3% GDP practically through their entire history of EU membership. They have seen the Commission Excessive Deficit Procedure applied and have in fact done hardly succeeded in reducing the deficits.

Three of the countries saw high growth in the past year or two, not seen since the mid 1990s. If this boom were accompanied by a counter-cyclical fiscal policy, we would expect governments to use public spending in order to smooth the cycle, and automatic stabilizers should guarantee the primary balance to improve. However no such pattern can be observed.

Precisely when the economies are booming, is the time to sort out public finances - exploiting the high growth would allow this to be done less painfully. But with high levels of optimism, and politically week governments caving in to populist pressures the motivation is lacking. Looking at the graphs below we see that the high GDP growth is by no means met by a reduction of general government primary deficit relative to GDP. The politicians seem to be foregoing a perfect occasion to relatively softly sort out their public finances, to fulfill their EU obligations under the SGP and to prepare to join the EMU. There seems little preoccupation that once growth slows deficits may turn out unsustainable, while the social price of cutting spending will be much higher.

The above argument applies to three of the countries, while Hungary is in deeper trouble mainly because of caving in to temptations to loosen fiscal policy in the past (links below).

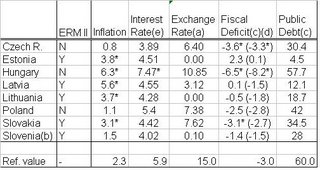

As we often emphasize, all EU member states are required to join the EMU. Aside Hungary, the three CEECs breach the Maastricht requirement solely on the fiscal deficit criteria (assuming reasonable central exchange rates for the Czech Republic and Poland which are not in the ERM).

The Czech Republic and Slovakia are in a more favorable situation from one point of view – the public debt, though the demographic outlook is similar to the other two states. The debt to GDP ratio in Czech Republic and Slovakia is well below 40% and thus rather far from the Maastricht requirement of under 60%. In Poland public debt will exceed 50% this year (according to the budget plan, Polish methodology) and there is a strong chance it will keep increasing further. In Hungary the situation is most problematic, as the ration is well in excess of 60% without much prospect to decrease in the near future.

Altogether there does not seem much prospect of the EDP being lifted in 2007 and 2008, for the three countries not in the ERM, while Slovakia, if it continues to be serious about joining the euro in 2009 will be forced to reduce the deficit.

Czech Republic

Growth in 2006 was strong, topping 6% and should continue though perhaps at a slightly slower pace according to Commission forecasts. The Czechs saw growth in excess of 6% for two years in a row - the first years of such growth time since transition begun. In early January this year, the Czech government was finally appointed after a 7 month crisis due to inconclusive election results. Despite this, the parliamentary support of the government remains fragile, what obviously causes any serious fiscal consolidation to be hard to expect.

Hungary

The situation in Hungary is certainly the most troubling of the four CEECs and has been reviewed extensively on this blog (here, here and here) and the cuts will need to be more drastic than in the other countries if a major crisis is to be avoided. Generally the government committed to reducing the huge primary balance deficit starting 2007, but the promised figures have since been questioned (see for instance IMF).

Furthermore growth is slowing down, and expected to slow further which will make the necessary reforms harder to push through given the political fragility which surfaced in 2006.

Poland

The yoy growth rate in 2006 was the highest since 1997 and is expected to increase further in 2007. As for being in the growth phase of the cycle, there seems relatively little preoccupation for the high amount of fiscal spending. Certainly despite the repeated promises to reform the fiscal spending (from the Minister of Finance), there seems little improvement and the support of the rather populist parties seems low. Though a major slowdown is not expected in the coming 2 years, reducing spending will certainly be more painful once the economy is developing slower. Moreover, serious reforms have been postponed (according to government declarations) to 2009 which seems hardly credible given that this should be an election year.

Slovakia

Despite a record of high, accelerating growth since 2000, which reached 6.7% in 2006 and is expected to further accelerate in 2007, the primary balance of the Slovak general government account hardly improved since 2003. Admittedly it is despite the increase last year, the primary deficit remained the lowest among the four states, but as Slovakia is the only of them aiming seriously to join the euro in the near future (2009) much more will need to be done taking advantage of the booming economy.

All graphs: BLUE - GDP growth % yoy, PURPLE - GG primary balance as % of GDP.

All graphs: BLUE - GDP growth % yoy, PURPLE - GG primary balance as % of GDP.Data Sources: Eurostat, Eurostat Euro indicators 03/2005 for data 2000-2001 European Commission estimates/forecasts for Convergence Program Assessments (latest) for 2006 and 2007. For Poland the Eurostat methodology was used (Polish methodology excludes pension reform costs and the primary balance improves) in 2000-2003 2% of GDP was subtracted from the primary balance (Polish methodology) in order to proxy for the costs.

Table 1. Tax rates in “flat tax” CEECs (

Table 1. Tax rates in “flat tax” CEECs (